The impact of organoid research on popular culture is nowhere more evident than in the common ground between innovation and animal rights proponents. Organs-on-chips harbor the potential to reduce animal testing of new drugs and cosmetics. In 2017, the U.S. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences funded 13 institutions with awards to develop tissue-on-chip models. Several of the awards mirror four-legged friends’ enduring goals.

Muscle disease is one example. One of the NCATS awards is for “Systemic Inflammation in Microphysiological Models of Muscle and Vascular Disease.” This Duke University project focuses on skeletal muscle and blood vessels. The models will replicate inflammation, in order to assess variation in responses to drugs. A similar award went to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center for “Development of a Microphysiological Organ-on-Chip System to Model Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Parkinson’s Disease,” to highlight novel biomarkers. There is no cure for ALS, a neurological condition that stops voluntary muscle movements including chewing, walking, talking and ultimately, breathing. Animal rights proponents welcome these endeavors because they have been vexed for years by the use of dogs for research that leaves them crippled with muscular dystrophy and unable to walk, swallow, or breathe.

“For decades, generations of dogs have suffered and died in gruesome experiments that haven’t led to a cure for muscular dystrophy in humans,” proponents claim. They have also campaigned against the use of birds in related neurotransmitter research, as being “cruel and pointless” while not yielding usable information.

Harvard University researchers received another of the NCATS awards, to develop “Lung-on-a-Chip Disease Models for Efficacy Testing.” Microfluidic organ-on-chip devices replicating influenza virus infection will be used to define new antivirals. This influenza disease model will be linked to human liver chips, to conduct pre-clinical safety testing of existing antiviral drugs, and to identify new therapeutics that target the host response to infection, rather than the virus itself. This too is a welcome mission for animal rights workers, because lung organoids help “scientists get a much better idea of how human lungs respond to airborne substances than they can by forcing animals to inhale chemicals and then trying to apply the results to a completely different species.” Moreover, it could mean an end to animals“ being forced to inhale toxic chemicals for hours at a time before being killed.”

Source: pixabay.com

University of Washington teams received an award to investigate “A Microphysiological System for Kidney Disease Modeling and Drug Efficacy Testing.” Chronic kidney disease affects more than 20 million U.S. adults and is the ninth leading cause of death in the U.S. UW scientists will create in vitro models that mimic critical aspects of kidney function, response to injury, and repair. They will architect “virtual clinical trials” for candidate drugs.

A related project award is “Kidney Microphysiological Analysis Platforms to Optimize Function and Model Disease” at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Microfluidics, stem cell biology, microfabrication and bioprinting will be used to model kidney diseases, and to screen for kidney toxicity. Kidney disease research historically relies upon multiple types of animal studies.

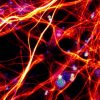

Two of the NCATS awards target heart functions. They include “A 3-DIn Vitro Disease Model of Atrial Conduction,” a University of California Davis project utilizing patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. “Drug Development for Tuberous Sclerosis Complex and Other Pediatric Epileptogenic Diseases Using Neurovascular and Cardiac Microphysiological Models” at Vanderbilt University will formulate neural and cardiac tissue-chip models that replicate drug response more reliably than those currently in use. In a 2017whistleblower case, a Veterans Affairs employee reported mistreatment of dogs being used for cardiac research.

The experiments he alleged included induced heart attacks. Many of the dogs died at project conclusion, and sometimes their hearts were harvested for further research.

The actions of the whistleblower, himself an Iraq veteran, drew several responses from the VA, some of which read in part: “At VA, we have a duty to do everything in our power to develop new treatments to help restore some of what veterans have lost on the battlefield. One of the most effective ways for VA to discover new treatments for diseases that affect veterans and non-Veterans alike is the continuation of responsible animal research . . . While there are ethical concerns associated with conducting animal research, they are far outweighed by ethical concerns associated with not doing animal research. The broad consensus of medical and scientific experts in the United States and around the world is that animal research is necessary. That’s why VA will continue conducting animal research like someone’s life depends on it — because it does.”

There’s no debating that most life-saving medical treatments were developed around animal research, including insulin, liver transplants, numerous cancer drugs, nicotine patches and pacemakers. Can scientists shift away from the baked-in pull of history? Animal activists have been buoyed by celebrity support, including comedienne Lily Tomlin’s efforts to defang their image as humorless fringe players.

Will organs-on-chips stop animal testing of drugs? Perhaps some of it, but not all. “It’s an illusion to think they can be used to completely replace animal research,” biologist Jurgen Knoblich told The Scientist in 2016.

Alternatively, “The key to staying hopeful is to operate on an assumption of success rather than failure,” Friends of Animals President Priscila Feral writes, summing up the perspective of many other activists.

While the pace of advance accelerates, it’s unknown which of these two predictions will prove realistic. But one thing is certain: NCATS’support for organs-on-chips energizes animal lovers’ central hope — that this horse is out of the barn.

Enjoyed this article? Don’t forget to share.

Kathy Jean Schultz

Kathy Jean Schultz is a freelance medical science writer who focuses on medical innovations. She earned a Master’s Degree in Research Methodology from Hofstra University, and a Master’s Degree in Psychology from Long Island University. She is a member of the National Association of Science Writers, and the Association of Health Care Journalists. Her articles about organoids include "Would you trust a 3-D printed mini organ to test your drugs?" and "Stem cells not only slow disease, they come with their own safety test".