Microfluidic engineering advances sustain organoids and fuel the growing stream of organoid uses. As tiny replicas of human organs, organoids are generated layer-by-layer from stem cells, and realistically vascularized by microfluidic systems, enabling life-like blood flow and other fluidic systems. Stem cells nurtured under specific three-dimensional conditions have produced organoids that replicate the architecture of the organ from which they were derived.

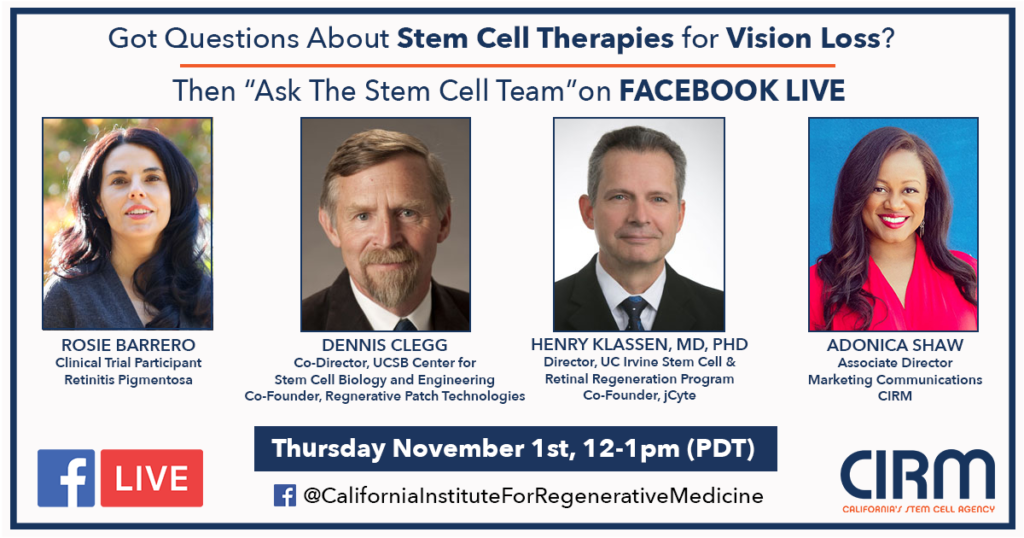

“Organoids are useful in retinal stem cell research,” said Dr. Dennis Clegg, a pioneer in the use of stem cells to reverse blindness resulting from age-related macular degeneration, during a live-streamed November 2018 “Ask the Stem Cell Team” webinar hosted by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Clegg explained how IPS (Induced Pluripotent Stem) cells can be donated by patients with a mutation that causes the blind condition called Retinitis Pigmentosa, or RP, and then used to generate organoids.

“Ask the Stem Cell Team” webinar was hosted by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine in November 2018.

“It is possible to make a retinal organoid,” Clegg said. “An organoid is organ-like so it’s not exactly like retinas, but it is very useful in research. You can take an IPS cell from a patient who has a retinal disease and make retinal organoids. It’s not exactly like the retina but it’s similar. It’s useful in research; you can take an IPS cell from a patient, make that cell into an organoid, and compare it to a normal, non-mutated cell.”

Clegg is founder of the University of California Santa Barbara Center for Stem Cell Biology and Engineering, a Co-Principal Investigator of The California Project to Cure Blindness, and a National Eye Institute lecturer.

Organoids are helpful because they mimic the layered structure of the eye’s retina. Organoids might yield a population of cells “that may be useful for treating disease,” according to Clegg. “If you are going to try to replace the photoreceptor cells that are perishing in a patient’s eye, you could even build a layered structure — an organoid — in the lab and then implant that to rebuild that retina.

“Patients become legally blind when they’ve lost both the rod and cones, the eye’s photoreceptors,” Clegg explained. In a clinical trial, “We started with patients who’d lost photoreceptors. The goal was safety. We wanted to show our process is safe. For patients who were lacking photoreceptors, the surprise was that some patients showed improvement in vision. We’ve shown it’s safe and we think if we catch the disease early enough, we can rescue photoreceptors.”

The use of microfluidic-sustained organoids is in many cases more applicable to humans than the use of experimental animals — and avoids ethical conflict. “For many aspects of research there are no good animal models, and retinal research is one of them,” Clegg noted. “You could even screen for drugs that might improve that retina-in-the-dish, and that would greatly speed up drug testing.”The webinar highlighted what cutting-edge advances are on the horizon, with other “Stem Cell Team” members Dr. Henry Klassen, and clinical trial volunteer Rosie Barrero. University of California Irvine’s Klassen is also a long-time researcher into the use of stem cell treatment to restore vision to people blinded by degenerative eye disease.

Some of Barrero’s vision was restored during a clinical trial. Klassen explained that volunteers like Barrero can describe what they see and what they don’t — which animal subjects cannot do. “We learn a lot more listening to Rosie than what our experimental rats could ever tell us,” he said. “It’s a wonderful surprise to hear these good reports coming from patients. I think we’ve all heard how cancer was cured in a mouse and then does not work in humans.”

Throughout her childhood, Barrero had steadily lost vision in both eyes due to RP — inherited and incurable. “I did not have night vision, I was very near-sighted, very myopic,” Barrero said. “My parents were protective and careful, they took care to not let me get into situations where I would injure myself. I did not know why.” As an adult, after giving birth to twins, she noticed a significant loss, which worsened after her next pregnancy. “After my third child was born I lost central vision.” She felt devastated to know she was going blind. She could not read, and by the time she met Klassen, “I had gotten to the point where I lost hope.” She volunteered for a 2016 trial.

“Rosie’s retinas were pretty beat up and she was blind,” Klassen said. “For her to see something coming back is a bit astonishing, really.”

“I received one million stem cells in the first injection,” Barrero said. “I have seen the most improvement from that first injection. I was blind and now I can see peripherally. The procedure was simple and lasted just a few seconds. I do not have a central vision but I can see out of the side of my eyes. It’s the simple things — I can see color. Before it was blurred, but now I can see colors through my periphery vision.

“When I received the stem cells I really noticed a huge jump in my vision,” Barrero said. “Even if it was just peripheral.” For the first time, “I’ve gone running with my daughter, and I look to my right somewhat. She tells me where there’s a branch or something to avoid. I can’t run on my own, but I can see on one side on my own, which is incredible.”

Live-streaming viewers were able to submit questions, and one person who submitted comment was one of Barrero’s children. She wrote: “Hi Mom. I hope you’ll still want to go shopping with me when you can fully see the price tags and don’t need me anymore!”

Enjoyed this article? Don’t forget to share.

Kathy Jean Schultz

Kathy Jean Schultz is a freelance medical science writer who focuses on medical innovations. She earned a Master’s Degree in Research Methodology from Hofstra University, and a Master’s Degree in Psychology from Long Island University. She is a member of the National Association of Science Writers, and the Association of Health Care Journalists. Her articles about organoids include "Would you trust a 3-D printed mini organ to test your drugs?" and "Stem cells not only slow disease, they come with their own safety test".