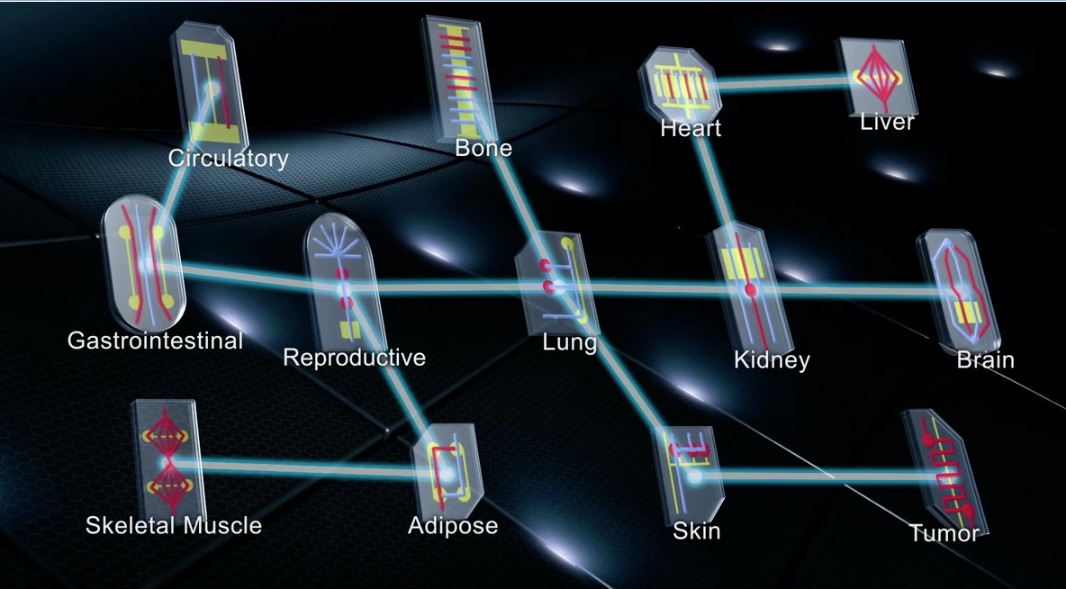

Names carry weight. The names of prestigious institutions and prolific scientists offer credibility. So to do scientific (and pseudoscientific) monikers: “double-blind clinical trials” assure integrity through rigour, and “superfoods” assure immortality through public misconception. As with “superfoods,” are we too prone to letting our imaginations run wild with scientific hype? Human- and organ-on-a-chip technology commands attention with its abundant potential in drug development and disease research, but also with its name’s sci-fi mystique.

Buzzwords aside, this microfluidic technology’s potential is very real. So real, in fact, that the United States Food & Drug Administration (FDA) launched a partnership with an organ-on-a-chip company in 2017. Understandably, increased success and commercialization makes organs-on-chips more accessible to scientists studying critical medical challenges. But it also encourages the oft-overlooked providers of elective health treatments to entice consumers with unchecked experiments and claims. This elective consumer space is less regulated and more vulnerable to abuse—especially when providers can deceive consumers with buzzwords teeming with scientific credibility. Organ-on-a-chip technology is a boon for novel experiments in labs, but only peer review and regulation can prevent its abuse by pseudoscientists.

Lessons from past malpractice

Without effective peer review, it’s easy to imagine dietary supplement manufacturers, for example, marketing the next snake oil based on staged microfluidics studies. In the United States, so long as the manufacturer does not explicitly claim its products cure disease, FDA regulation is not much of a barrier. This could practically pave the way for misleading advertisements: “Do you get TIRED at night? Our HUMAN-ON-A-CHIP studies PROVE this supplement is RIGHT FOR YOU!” The only thing protecting the consumer from deception, in this case, is peer review.

Unfortunately, deceptive marketing is not just a malevolent step-child of promising research, it is indelibly bound at the hip. Look no further than “stem cells” for proof. Stem cells can be pluripotent, meaning they can give rise to nearly any type of cell in the body. Their discovery has had a monumental impact on the future of regenerative medicine. But even before scientists devised a method to make pluripotent stem cells more ethical and accessible, this buzzword carried connotations of “miracle cells.”

Fast-forward to 2018, and the FDA has had to crack down on so-called “stem cell clinics” that endanger patients with elective stem cell injections for various ailments. Aside from being risky, these cell-therapy procedures are unproven—the cells used are often extracted from the patient’s fat and are not even pluripotent. This business model works well enough to warrant FDA involvement, but not well enough to prevent patient harm. These clinics ride the coattails of legitimate stem cell research and profit from the power of a buzzword. Unfortunately, consumer and patient exploitation are inevitably tied to commercialization, and it is fair to say that no accessible technologies—especially groundbreaking ones—are immune.

Organ-on-a-chip technology has become drastically more accessible. Two years ago, I had zero experience with microfluidic or biological research. Today, I spend the majority of my time designing organ-on-a-chip devices and experiments. The barrier for entry is low—I could plan a simple experiment and successfully grow human cells on a chip. But without the scientific expertise and integrity of the women and men around me, drawing worthwhile and reproducible conclusions that hold up against peer review would be infeasible. The danger with buzzwords is that they can only be policed by public caution and skepticism. As this technology becomes more popular, the scientific community should emphasize peer review and regulation in all of its applications.

Some room for optimism

All of this is not to say that organ-on-a-chip commercialization is anything short of revolutionary and, well…good. Patients stand to benefit tremendously from new treatments and fundamental knowledge. Hesperos and Emulate, two commercial pioneers of the field have numerous collaborations in the healthcare industry. Hesperos provides a platform to accelerate drug development, and Emulate hopes to break new ground in personalized medicine with their “patient-on-a-chip” initiative. Organ-on-a-chip technology has also played a role in advancing novel treatment methods. Recently, researchers at Harvard’s Wyss Institute developed a chip that allowed accurate modeling of a portion of the human kidney using pluripotent stem cells. This work opens doors for repairing damaged kidneys—offering a legitimate stem cell therapy.

Because these are cases of medical and pharmaceutical research, peer review and regulation (in the form of double-blind studies) will have the ultimate say. The elective consumer space is more of a gray area. Fortunately, we have an opportunity to treat it with comparable scientific rigor. The FDA could one day choose to mandate using organ-on-a-chip devices for safety testing of dietary supplements. Microfluidic experiments are significantly cheaper than animal or human trials, and this may make evidenced-based policy more feasible. We could also one day request the use of organ-on-a-chip platforms to validate risky cell-therapy procedures before experimenting on live patients. If we don’t lose sight of peer review and regulation as governors of science, we can validate market claims to benefit the consumer. Reliable public scientific data, in a space where not much exists, allows us to address the credibility of lofty claims rather than to leave them unchecked.

There is an undeniable magnetism inherent to buzzwords. They attract media attention and research funding, but also opportunists, hucksters, and charlatans. To this point, we have had to take the bad with the good. Fortunately, we can learn from ongoing malpractice and arm ourselves with the most impenetrable shield in a scientifically literate society: skepticism.

Featured image credit: NCATS

Enjoyed this article? Don’t forget to share.

Max Levy

Max Levy is a Ph.D. student at the University of Colorado Boulder studying chemical and biological engineering. His research focuses on the intersection of nanotechnology and drug development. He also serves as a science writer, and as a senior editor for the "Science Buffs" blog.